HGA Arts & Culture experts weigh in on the future of museums in this ongoing series, Museums Emerging from the Pandemic.

People are craving community. As America moves toward reviving its economy, close on the heels of the worst pandemic to strike the nation in over a century, many museums will reopen before a coronavirus vaccine has become widely available. And although museums are beloved destinations—they welcome people of all kinds, put our world in context, and often provide unbiased explanations—in this light, how might museums prepare to best protect their visitors and staff from infection while reopening their facilities?

Timed Tickets & Limited Capacity

Many museums already use timed-entry tickets to manage crowds visiting popular traveling exhibitions. Emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, timed ticketing will help large capacity museums carefully manage how many people are in their facility at any one time without generating lines of anxious visitors outside their buildings. Providing museums with a much-needed source of revenue, timed tickets can be sold online enabling a contactless process to protect staff that would normally interact closely with hundreds (or thousands) of people. Visitors arriving just before their assigned ticket times could be greeted with clear signage showing where they should queue, with clear markings on the floors or pavement to guide ample physical distancing.

Smaller museums without the large numbers of visitors needed to justify timed ticket sales can still streamline their entry sequence and protect staff. They could implement a distant display of membership cards for entry, reducing the number of people at the admissions desk where they can use Plexiglas shields, or allow card-only transactions administered by staff with proper Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). The floor near ticketing should be marked to guide physical distancing by the current standard of six feet or more.

Timed arrivals could also be applied to museum staff, providing staggered shifts for when they can be in the building. This would allow for a reduced and carefully managed occupant capacity throughout the museum.

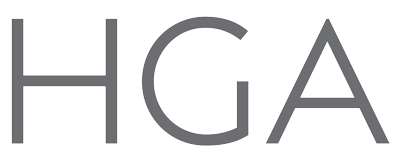

These considerations raise the issue of what the revised capacity of public buildings should be moving forward. Currently there is no coordinated policy or common standard for calculating maximum capacity—each museum must find its own tailored solution. Restricting capacity is a dynamic challenge with a range of implications that depend on variables such as museum type, geographic location, time of day and season, size and configuration of galleries and resulting pinch points, dwell times, degree of physical openness, whether visitors are traveling as individuals or part of a household group, local government restrictions and CDC guidelines, etc. Each of these considerations can be analyzed to inform a customized visitor-per-square-foot formula, allowing museums to control visitor numbers and limit person-to-person contact in a way that suits their specific operational needs.

Extra thought for elevators in lower traffic areas can be taken to discourage use when not essential, allowing visitors with disabilities to feel safer and welcome. In high throughput attractions where elevators are part of the primary visitor path, precautions other than precise physical distancing will need to be clearly communicated, particularly when proper physical distancing is not possible to achieve.

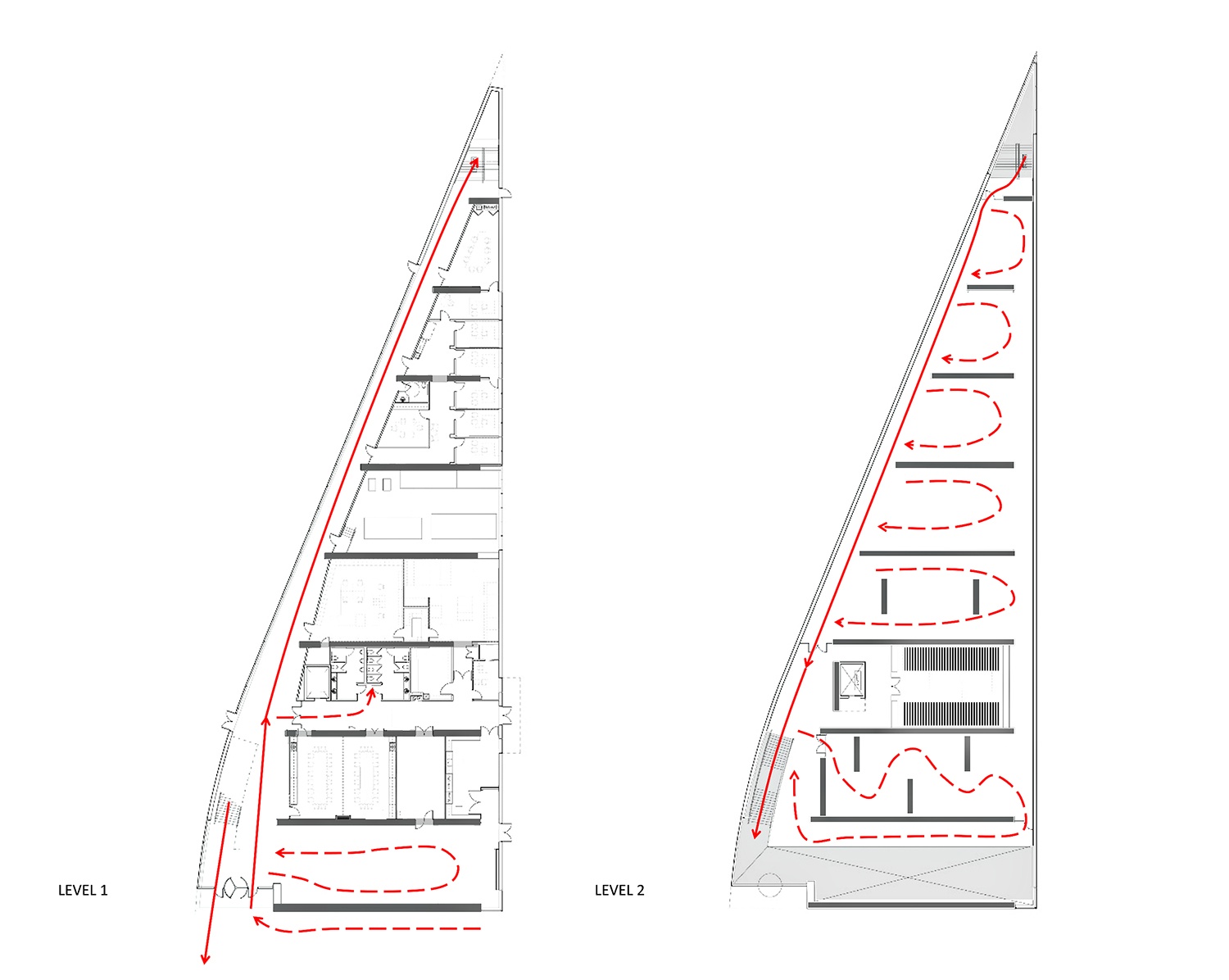

One-Way Circulation & Comprehensive Wayfinding

If all visitors are asked to move through galleries in the same direction, safe physical distancing can be more easily maintained. This system is already widely used in galleries with rotating exhibits, with a single point of entry and exit, and typically a single prescribed route through the gallery. Applying this strategy to an entire museum can greatly reduce unavoidable close contact. Plans with one-way circulation patterns can be developed using furniture, moveable walls, or stanchions and ropes to curtail random movement and unexpected close contact. Gallery maps can be made available online and be accessible to visitors via their smartphones.

Communicating local or regional health guidelines and museum policies, including improved wayfinding, should be practiced both inside and outside the museum. While tape on the floor is effective, thoughtful and clever brand-building environmental graphics could be used to help communicate physical distancing guidelines and clear wayfinding. Research shows that new directional signage needs to be extra bold and stand out from existing permanent wayfinding to avoid confusion.

Building and maintaining public trust will play an increasingly large role in attracting visitors to cultural institutions. Visitors want to know and understand how these places are protecting them. Clear, consistent, and creative communication will help them feel safe and possibly lead to visitors recommending the museum to family and friends.

Leveraging Outdoor Space

As evidenced by the public flocking to parks and trails, museums can re-think their outdoor spaces to host services, gallery talks, events and programming. Spaces that offer freedom of movement are likely to see increased visitors soon because of the perceived safety of the outdoors according to Colleen Dilenschneider. More innovative programming for outdoor spaces and activating building facades for public gathering and community engagement could help draw visitors, particularly in the warmer months and shoulder seasons. These spaces could also provide opportunities for partial or soft openings as well to manage crowds. Expanding audio and visual systems to support outdoor programming are a key consideration for reopening museums. These systems can be less expensive, temporary solutions to meet visitors’ expectations.

Online Programming

Since the national lockdown, many museums have been forced to cancel or postpone in-person gallery talks, lectures, live demonstrations, and classes. By nature, these events demand a close physical proximity between attendees which now put visitors, staff, and artists at risk. Many museums have rapidly shifted to online programming, such as virtual artist talks and digital galleries, that can be streamed across a variety of platforms and have been widely embraced by those looking for a diversion from at-home isolation. Two new hashtags have been mobilized by museums, #MuseumFromHome and #MuseumMomentofZen, enabling them to reach a much broader audience. One of the most successful examples of digital engagement comes from the creative partnership between Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Kansas City Zoo, who collaborated to let the zoo’s penguins wander through the art museum’s galleries. The event’s live stream was shared on social media and quickly went viral, providing a delightful source of entertainment for viewers as well as much needed enrichment for the animals.

Placing more programming online is difficult to monetize but has allowed museums to reach a broader and nontraditional audience; people with underlying health conditions who are unable to visit the brick and mortar museum, as well as a more national, or international audience. Digital programming has opened a market for online events that will have a lasting impact well into the future. Bruce Karstadt, President and CEO of The American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, says, “Since the shutdown we have discovered that we have a broadly-distributed audience interested in participating in our programs, even remotely… Now we know that we have students who will enroll in on-line classes, and these students live in out-state Minnesota, in other states, and even in Germany!” For many institutions digital experiences may very well become the new normal.

Key Considerations for Reopening Museums

- How might you build visitors’ anticipation for their coming visit, ensuring with confidence that they will be taken care of?

- How might you communicate changes to visitors—especially members familiar with the space as it was—in a creative, engaging format in advance of their visit?

- How can you leverage artists to help translate health messages to inform and engage the public—making sure to consider all cultures and languages in your city?

- How will institutions remove the fear of returning to museums through clever, mission-driven graphics?

- Can more outdoor projections be employed for film and video content or open-air discussions previously occurring in auditoriums?

Contributors

HGA experts: James Shields, FAIA; Joan Soranno, FAIA; Marc L’Italien, FAIA; Leighton Deer, PE; Nancy Blankfard, AIA

Museum experts: Laurie Winters, Executive Director, Museum of Wisconsin Art; Walker Art Center; Bruce Karstadt, President and CEO, American Swedish Institute

Read Part Two: Building Systems and Part Three: Hands-on Learning. If you have questions or comments about this piece, please contact Amy Braford Whittey, National Business Developer for the Arts.

HGA has created a hub for our insights and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic as architects, engineers, interior designers, and problem solvers. Follow the conversation here.